Understanding pandemic work and the limits of war language

As we pass the sixth month of the Covid-19 pandemic, amidst new cases in the United States continuing to spread and a second wave of infections in Europe and Asia, 2020 is feeling less like a winnable battle and increasingly like a long siege: isolation without end; flagging mental, physical, and capital reserves; dire economic and health tradeoffs. Some kinds of work have been deemed “essential,” and workers are called upon to serve and fight despite personal risk of infection.

The media tells one story: Doctors and workers going to war against an invisible enemy. While widespread and compelling, this rhetoric is a limited view of how the pandemic has shifted the job market and our conceptions of work.What does the data show about essential workers and how we talk about them? How can language data help us understand this brand-new category of jobs at the “frontlines” of the pandemic, and how might society value them differently in the future?

Data reveals that the job market is responding to the crisis not by asking for sacrificial healthcare warriors, but for sustainability across the economy—from an increased need for loan officers due to the ensuing recession to more listings for network engineers as whole industries move to remote work. Skills like care and compassion are on the rise. Unity, solidarity, and civic service—not animus—fill jobs faster.

A pattern of militarizing health

If we take a moment to understand why we think about the pandemic in terms of military metaphors, it may come down to the rhetoric we’ve been seeing in the news and from government leaders. At the height of the Covid-19 case surge in New York this March, Governor Andrew Cuomo used the war metaphor extensively during a press conference:

“The soldiers in this fight are our health care professionals. It’s the doctors, it’s the nurses, it’s the people who are working in the hospitals, it’s the aids. They are the soldiers who are fighting this battle for us.”

In April, Canadian newspaper The Globe and Mail published an op-ed with the headline, “We are at war with COVID-19. We need to fight it like a war.” And in May, Donald Trump compared doctors and nurses to warriors, describing them as “running into death just like soldiers run into bullets.”

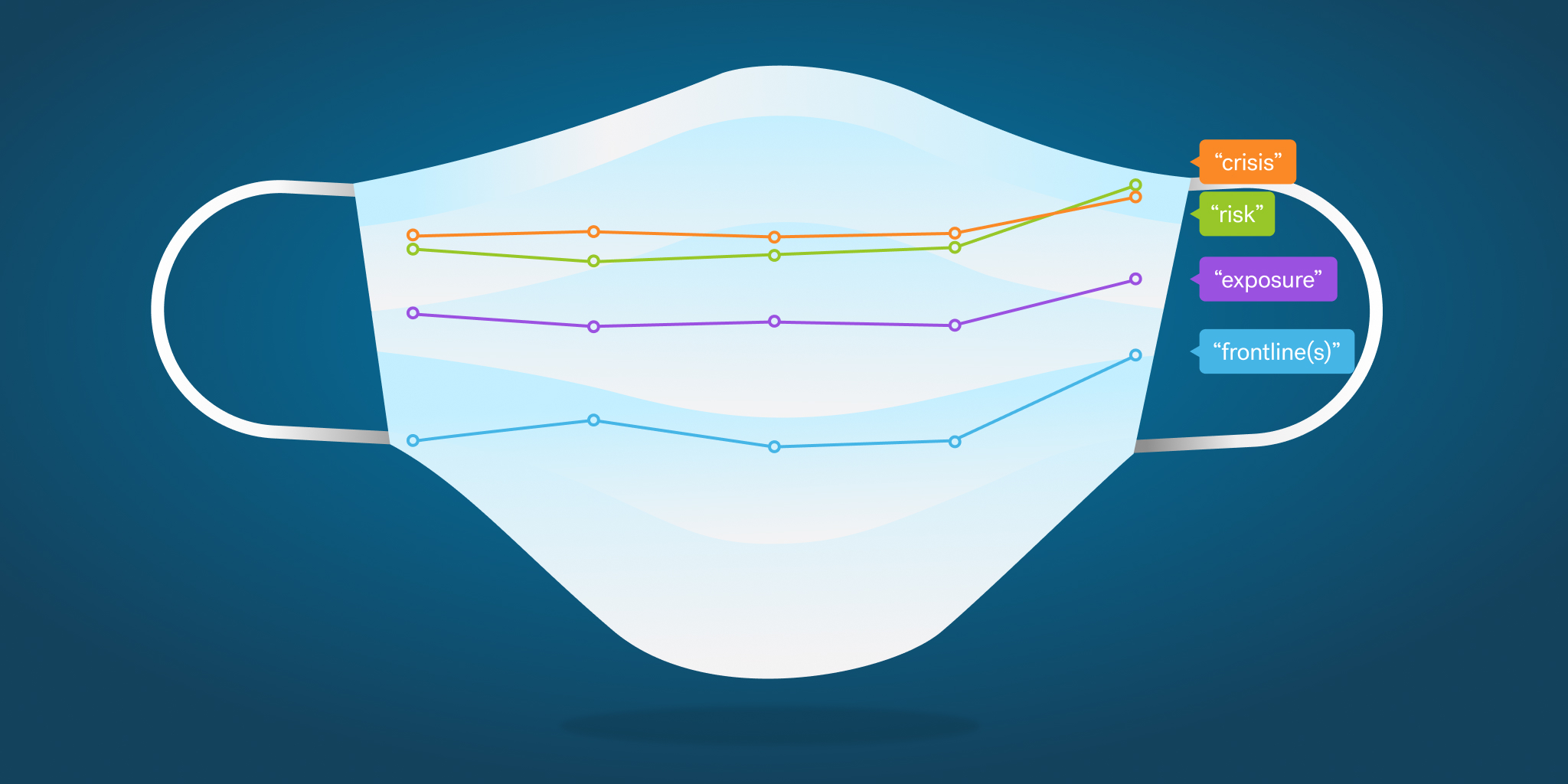

These examples aren’t just one-offs, but part of a measurable pattern. In the media, language of frontlines, risk, and exposure, has jumped in 2020 to levels not seen in the last five years. In fact, mentions of not just any war, but the biggest conflict in recent history, World War II, have nearly doubled in March of this year, as journalists and pundits compare this pandemic to that deadly benchmark. For the same time period in previous years, no week ever mentioned World War II more than 127 times, based on Textio’s sample. During the week starting March 22, 2020, the war was mentioned 231 times.

In particular, newspapers have placed a new burden of this warlike comparison on essential workers. When essential work is mentioned in a piece, the phrase also co-occurs with crisis, war, fight, and frontlines in at least 1 out of every 10 articles in March.

Essential work: a brand new category

We looked at a sample of 2.7 million newspaper articles from the last five years to understand the origin of essential work. Before March 2020, essential work as a category of occupation neither existed in the media, nor in the general consciousness. But with the onset of so many shelter-in-place orders across the world, a subsection of jobs were deemed “essential” for the continued function of society, even as society retreated to their homes.

In the months leading to December 2019 to February 2020, there were only 1-2 articles per month that contained the phrase essential work and its variants. By March 2020, it had already jumped 40-fold, to 87 articles. Similarly, hazard pay began showing up regularly for the first time, jumping from effectively 0 mentions every spring to 108 mentions this February and March.

But if you were to only look at how newspapers talked about essential jobs, you may come to the conclusion that only doctors, nurses, and healthcare workers were “essential.” This spring the newspapers were full of the plight of hospitals. Since the beginning of the pandemic, coverage of healthcare workers, doctors, and nurses, has expectedly tripled, if not quadrupled.

The reality is not just risk and heroism, but also support and care

Textio looked at more than 86,000 job descriptions from April 2019 to April 2020 to understand the effect of the pandemic on jobs. Two groups of skillsets in particular pointed to an urgent need in the job market, but aren’t restricted to the image of the embattled healthcare workers that the media so often portrays.

One specific set of skills saw a jump between February and March as the recession began in earnest: insurance, billing, and loan administration.

Another set that showed pandemic-related growth is in IT, as non-essential workers transitioned to remote work all over the world:

Finally, a soft skill like compassion saw a 24% increase in job posts between February and March. While many similar words like empathy and enthusiasm have dropped during this same period, compassion is growing in importance.

The job market reflects the state of the world, and this data about the jobs that are on the rise shows that this pandemic is less about a war with an external enemy, and more about sustaining ourselves.

And this language doesn’t just show up in aggregates. In specific job posts from shipping to grocery, companies from Fedex to Kroger are using language of support and service:

The limits of the war metaphor

The problem with the pandemic war metaphor is that viruses, unlike armies, don’t surrender. Hospitals will likely remain full until we have a safe vaccine and a population who is willing to receive it, remote work will continue, and families and businesses will need financial stimulus and loans to stay afloat.

Instead, sustained unity, care, and support is required. But the good news is that this language works. In fact, when jobs use the phrase united by they fill 15 days faster. Job posts referring to working with the general public fill 3 days faster.

When we move away from political rhetoric and look at the language in more mundane documents like job descriptions, we see a vastly different portrait of who essential workers are, and how they—and workers in general—are coping with the pandemic. Rather than cultivating an image of soldiers at the battlefront, media and governments may be better off appealing to our sense of civic duty, care, and solidarity with our fellow human beings.